(a David lyric)

* * *

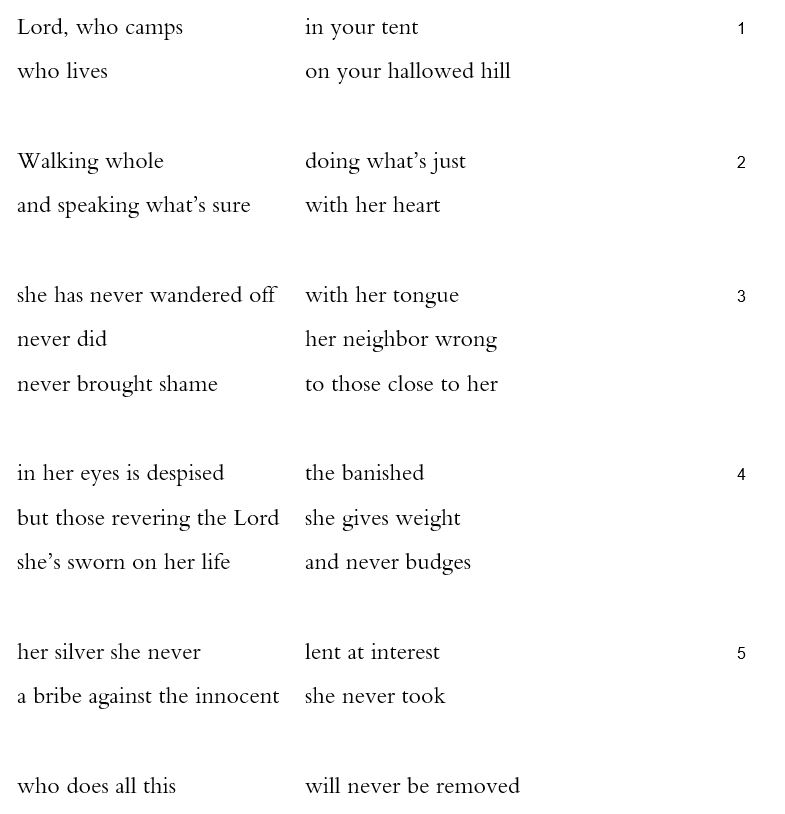

The most famous list of moral principles in the Hebrew Bible is certainly the Ten Commandments—or, rather, that group of injunctions, sometimes called the Ethical Decalogue, that appears with subtle differences in Exodus 20 and Deuteronomy 5. (There is a Ritual Decalogue in Exodus 34 as well.) Psalm 15 is an ethical decalogue all its own. It is not a series of apodictic commands in the second-person singular (“thou shalt” or “thou shalt not”). Instead, it’s a character sketch, defining the moral community by describing ten traits of goodness that a member needs in order to be admitted and remain in the Lord’s circle, “your tent… your hallowed hill” (1).

Written of a generic individual— third-person masculine in the text, third-person feminine in this translation— the psalm moves with clarity and precision through meticulously patterned principles. Verse 1 asks questions that the rest of the verses answer: in the tabernacle, later in the temple, still later, by extension and diaspora, in the grand circle of divine care, “who camps… who lives?” By the end of verse 5, a promise arrives: “who does all this | will never be removed” (5c).

Between questions (1) and promise (5) are ten traits grouped into three threes plus one, with six negatives (made a series of seven by the psalm’s last line: “will never be removed”). The definitional member of the community is a moral being who moves with integrity, who works for justice, and who speaks the truth: “Walking whole | doing what’s just / and speaking what’s sure | with her heart” (2). As participles, these three words work like a left-branching sentence, setting up the next group of three, all negated verbs in the completed tense: “she has never wandered off | with her tongue,” “never did | her neighbor wrong,” “never brought shame | to those close to her” (3). Each line tightens the last, from loose-tongued slander all over, to wrong among fellows, to making a mockery of intimates. Each also intensifies its correlate from the first trio, walking (2a) means not wandering off (3a; the verb ragal is denominative from the word “foot”), doing what’s right (2a) means not doing bad (3b; the verb ‘asah is used in both), and speaking truth with the heart (2b) has an intimacy fitting “those close to her” (3b).

The final group of three traits is also marked by perfective negations, things the good person has not done: broken her word (4c), abused the common wealth by seeking personal gain (5a), or used a broken economy plus a broken word to harm the innocent (5b). Again, in the last group of three, each “has not done” picks up on its correlates: “walking whole” becomes “not wandering off” which becomes “having vowed, she does not move” (4c); “doing what’s just” becomes “never did | her neighbor wrong” becomes “her silver she never | lent at interest” (5a); and speaking the truth in the heart becomes honoring those near which becomes, profoundly, honoring anyone innocent, no matter how close (5b). These three groups of three move from general traits of personal integrity to their consequences for others and for the social order. Integrity, fairness, fidelity to the truth—these three recur: twice generically (once by assertion, once by negation), and once more specifically, in how one treats others.

The seventh of these ten traits stands out. It’s unpaired, but presents a careful chiasm, a pivot for the entire list: “in her eyes is despised | the banished / but those revering the Lord | she gives weight” (4a-b). It pits how she, the model devotee, treats those outside the community against those inside. More particularly, her condemnation (nibzeh) of the nim`as, the one abhorred, “the banished” (compare 1 Sam 15:9, which links bazah and ma`as together to the root word cherem, the ritual ban), contrasts with how she treats the yireh-Adonai, “those revering the Lord.” This group are treated as a specific class throughout the book of Psalms especially (e.g., 22:23, 61:5, 135:20), and in a Hellenistic context are identified in Greek as proselytes, converts from other cultures and races (oi phoboumenoi ton Theon, e.g., Acts 13:16). The moral person’s valuation of these others, then, is as much about trajectory as about position: she esteems those who are moving towards and within, and spurns those who have moved (or been moved) out and away. She herself “never budges” (4c).

There’s something particularly ancient about this conception, perhaps, bounded by the tabernacle’s enclosures. But then every community defines its borders, some more explicitly than others. Few definitions are as taut and crafted as this psalm. Who gets to stay? Anyone who wants to, with integrity, fairness, and fidelity.

*

15:2 walking whole In Hebrew, too, the construction is participle + adjective: one who walks complete/sound/perfect/blameless. There’s a moral component to tamim, as there is to “whole,” but also a purely practical sense of healthiness, being intact, hale (which derives from the same root as “whole”).

15:3 wandered off | with her tongue The literal line is even more potent, “has not footed with her tongue.”

15:3 her neighbor wrong In Hebrew, a pointed pun: lerei’eihu ra’ah.

15:3 never brought shame Lit., “a taunt never lifted”

15:4 the banished The nim’as is perhaps a class of those who have been officially despised. See note above.

15:5 her silver she never | lent at interest The laws against changing interest in Exodus 22:25-27, Leviticus 25:35-38, and Deuteronomy 23:19-20 are clear, if distinct: it was illegal to charge interest on loans. The Exodus and Leviticus interest laws are both conditional, contextualized by poverty, though poverty is defined relationally— “any of my people that is poor by thee” (Exod 22:25) or “waxen poor, and fallen in decay with thee” (Lev 25:35). Whether people ever lent money to someone richer is a fair question. Deuteronomy removes the condition of poverty, but adds that charging interest to non-Israelites is legal (25:20).

The backbends that commentators do, trying to justify modern economies by qualifying this proscription against charging interest, are impressive. “The prohibition of interest looks more to charitable loans made to the poor… to relieve distress than to purely business transactions” (Dahood 84). Kraus says, without evidence, that the line means “to be helpful with the proceeds of a loan and not to practice usury” (230). “In a commercial society where money is a commodity, interest becomes acceptable as a price paid for goods and promotes business ventures. Any commodity demands a price. When money is viewed as a commodity it is also entitled to a price. Interest is nothing more than the price paid for money. This was not the view shared in the biblical world,” say Rozenberg and Zlotowitz (74).