(of David)

* * *

Nearing its end in Psalms 138-145, the Psalter returns to the figure of David. A surprising number of readers have seen this string of psalms with David’s name in the superscription as evidence of a programmatic messianic eschatology. From these psalms especially, they build an argument that the book as a whole promotes the return of a Davidic king who will rescue Israel from its oppressors. These eight psalms, however, only get anywhere near eschatology or apocalyptic imagery in a single part of Psalm 144 and only sound remotely messianic like Second Isaiah or Zechariah in one part of Psalm 143. And yet, overall, they present David not as a king whose line is to be restored, not even as a priestly king, but as a model of worship at the temple he himself never saw. If anything, this run of psalms seeks to contain and control disruptive messianism, displacing it with appropriate piety.

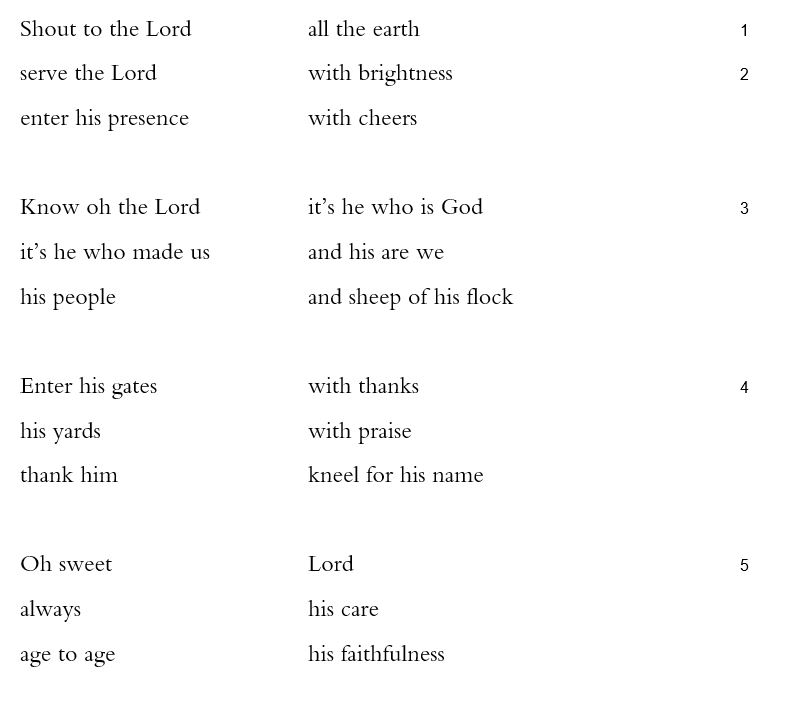

The first of the sequence, Psalm 138, lies between two of the most vivid and memorable poems of the entire Bible, a less-than-favorable position for a psalm so choppy and tricky to parse. Psalm 138 relies on the handing-off and expanding of images, which amplify and complicate the speaker’s gratitude. This gratitude is already complicated at the beginning, given that the speaker thanks an unnamed “you” who is in front of or over against or “in the face of” ’elohim, either “God” or “gods” or both. Like Psalm 137, Psalm 138 depends on the range of the repeated preposition `al. The speaker expresses the wish to “thank your name | even above your care / even above your loyalty | for you grew / even above all | your name your word” (2b-d). Using “even above” for the single syllable `al aims at the Hebrew word’s potential to mean elevation, superiority, and reliance all at once. The speaker thanks “your name” on top of, both more than and because of, “your care” and “your loyalty.” Paraphrases of this look like logical flowcharts, both meticulous and a mess: I thank your name more than your fidelity and care because it rests on them and because you made your word even bigger than your name—or, because you made your name and your word even bigger than everything. Hard to put any other way, these three lines gesture towards and above, seeming to indicate both intimacy and God’s ability– because of and beyond loyalty and caring, name and word– to exceed even God.

At the center of the psalm, this exceeding and making-great— translated here as “growth,” the most obvious way in which life exceeds itself (2c, 5b)— spreads beyond the speaker to “all the kings of earth,” who “have heard | the words of your mouth” (4). The speaker’s thanks give way to theirs. In “They thank you Lord,” the Lord is named for the first time. The speaker’s song, too, gives way to others’ (“they” may or may not point back to those kings): “and so they sing | in the roads of the Lord / oh grown is | the glow of the Lord” (5). By verses 6 and 7, the lift and spread of the Lord has become universal. “Oh the Lord’s up high | yet sees the low,” the speaker or the others sing. From these heights, the psalm returns to the first-person singular, to the nameless “you” and to the exceeding `al, while borrowing from the poem’s middle the image of the road: “As I walk the center of sorrow | you give me life / even above my enemies’ rage | you reach out your hand” (7a-b). Divine “care” reappears (2, 8), as does the image of the hand (yod, 7-8), implicit earlier in thanking (yadah, 1-2, 4). The primary effect is to show both the continuity and the increasing of the Lord’s care.

Given the superscription, the psalm’s secondary effect is to associate the continuity and growth of divine care with David. If we take David as the speaker, then the psalm starts by having the monarchy bow to the temple, where the name of the Lord and the word of the Lord are celebrated— “oh they have heard | the words of your mouth / and so they sing” (4b-5a). The psalm then transfers that celebration of the Lord from one local king in Israel to “all the kings of earth” (4), returning to David, whose gratitude started what others continue. This point is explicit: “The Lord completes things | on my behalf,” (ba`adi) the speaker states (8a). The speaker’s part ends, in contrast with the Lord’s care, which is “always” (8b). Far from encouraging hope in a triumphant return of a Davidic king, the psalm ends by letting the Lord end things in David’s stead, keeping David in the role of a supplicant, praying to the Lord, “what your hands do | don’t let go” (8c).